Humanitarian Recession: A Simple Framework15 min read

Humanitarian Funding goes up, and humanitarian funding goes down. That’s a statement of the absolute obvious. But beyond that, it’s still confusing to actually understand in what direction things are going. We have a maze of figures. Everywhere we go there’s figures, figures, figures. Charts, charts, charts. On OCHA’s Financial Tracking Service, on Humanitarian InSight, in reports about funding. It’s dizzying.

But how much insight do we actually have about the global humanitarian funding system? Part of the reason behind this disorientation and migraine-inducing scenario, is the lack of language we have to talk about funding. Economists have words like inflation, interest rates, unemployment, money supply. Words that help distil large complex things into easy-to-understand concepts for the layperson.

One of those words is ‘recession’. A recession is an incredibly useful word to understand if the economy is either going in the right direction (growing), or going in the wrong direction (shrinking). And if we know when we are in a recession, we’re able to take mitigating actions: fiscal stimulus, lower interest rates, or quantitative easing.

In the humanitarian world, we don’t have this vocabulary. We don’t talk about ‘humanitarian recessions’, and we don’t have any policy levers to pull when the humanitarian economy is shrinking.

We’re going to make the case here that we should be a) using the term ‘humanitarian recession’, b) measuring when there is a recession in a humanitarian sector, and c) responding to humanitarian recessions with real world action.

And we’ll see that six sectors are in a ‘real recession’ right now, namely: Child Protection, Coordination and Support Services, Education, Health, Multi-Sector, and WASH.

Recession Digression

It’s generally accepted we want to see an economy grow. There are criticisms of this view: growth isn’t good in a world of finite resources, GDP is an imperfect measure, and happiness might be a better outcome metric, to name a few related critiques. But growth matters to economists because more economic output generally means more jobs, earnings, taxes, money for public services, and real consequences for real people.

In the humanitarian world, it’s the same. Increases in funding equal more jobs and volunteers, and more output for real people, i.e. humanitarian assistance and meeting humanitarian need.

Similarly, if an economy falters, then it affects policy. Fiscal policy may adapt: the government may spend more money to increase demand in the economy. Monetary policy may adapt: interest rates may be cut to manage falling inflation. And a whole host of other public policy options.

But we are able to do this because a) we know there is a recession, and b) “recession” signals to everyone that something needs to be done.

In the humanitarian world, it should be the same. If we know funding is declining, we can encourage people to pull a policy lever. We would be trying to ‘smooth’ the cycle of funding, making the falls in funding less severe, and the impact of that fall in funding less severe for affected populations too. But we can only do this if we know there is a recession, and if we have some policy levers to pull.

Therefore we’re going to need to know if there actually is a recession. In other words, has there been a fall in humanitarian funding which will then signal to everyone that something needs to be done. So, how do we construct a definition for a humanitarian recession?

Defining a ‘Humanitarian Recession’

What are we applying the term ‘recession’ to?

We’ll apply the term to the whole humanitarian sphere, and to specific global sectors, e.g. Nutrition, WASH, and so on. We could also apply it to individual contexts, but we won’t go into that for now. The whole humanitarian sphere and specific sectors have the benefit of being ever present. Individual contexts, e.g. Venezuela, or Libya, may have response plans one year, and then not the next. Sticking to things that are consistent over time simplifies things.

What do we include in our definition?

We’ll try to include all humanitarian funding as far as possible, so as to not arbitrarily exclude funding that has been contributed to a humanitarian cause in the real world. We want to really reflect the true state of funding.

But we will exclude a few things. Firstly, we will exclude pledges, as this is not actual funding anyway. Secondly, we will also exclude funding flows that aren’t tagged with one of the following: location, emergency, or response plan. This is important as if we don’t have any context to tie the funding to, we cannot be sure what the funding has actually gone. Thirdly, we’ll exclude multiple year funding as it’s impossible to disaggregate this to single year funding. And lastly, for sector specific ‘recessions’, we’ll exclude multiple sector funding as we cannot disaggregate to individual sectors. But we can keep this for the whole humanitarian total.

Do we need two definitions?

Going back to those critiques, the assumption behind this paradigm is that growth is good. Maybe governments should follow the Bhutan example – using the ‘outcome’ indicator of Gross National Happiness, instead of just an ‘output’ indicator of economic output. And maybe we should see growth in the context of the boundaries of our natural resources?

A parallel critique is easy to anticipate for humanitarian recessions. Growth in funding for humanitarian crises is not always good, as it means there are humanitarian crises… which we don’t want of course. If humanitarian need is shrinking, and therefore funding is, then that’s okay. If need is growing, but funding is growing faster, that’s also okay. So we need a definition that takes into account funding relative to need.

Therefore, we’re proposing two definitions:

- Technical humanitarian recession: negative % growth of all funding

- Real humanitarian recession: growth of funding < growth of funding required

In the second instance, if

- Growth in funding < Growth in funding required, then that’s a real humanitarian recession

- Growth in funding = Growth in funding required, then that’s stagnation

- Growth in funding > Growth in funding required, then that’s real growth

How long does funding have to drop for to constitute a recession?

One of the commonly agreed definitions, at least in economic textbooks, is that a recession is two consecutive quarters of negative growth. On the one hand, two consecutive periods of negative growth makes sense as it signifies a trend. However, instinct suggests that two quarters of negative growth wouldn’t really work for humanitarian funding as it’s much more volatile on a quarter by quarter basis.

What we’re looking for is a time period of negative growth that does three things. Firstly, it shouldn’t be so volatile as to make the meaning of ‘recession’ meaningless. A shorter time period equals more volatility in funding. Let’s take this to its extreme and imagine a humanitarian recession is defined as two consecutive days of funding. If ‘Day 2’ and ‘Day 3’ both had incoming funding of $0 compared to $2.5m on ‘Day 1’, we wouldn’t be saying much if we were to say there was a recession on ‘Day 3’. Especially in the humanitarian world, funding flows don’t happen everyday, particularly in smaller sectors.

Secondly, it shouldn’t be so long that ‘recession’ lacks meaning, or it never occurs. A longer time period equals less volatility, but also means that recession might not mean much. Taken to its extreme, imagine we defined a humanitarian recession as 100 years of negative funding. It would be extremely unlikely that this would ever happen, and so the framework would be pointless. It would also mean that shorter periods, say 5 years of negative growth, aren’t identified as recessions. We wouldn’t realise this at the time, and therefore would not take mitigating actions.

Thirdly, it should be a suitable amount of time that it feeds back into real world decisions about where to allocate resources. If we defined a recession as two consecutive five year periods of negative funding, then we would only be able to measure every five years. But if we we defined it as two consecutive weeks of negative funding, then that’s not giving enough time for real world decisions to feed into funding data.

Basically: we’re looking for a time period that is long enough to be not so volatile, and short enough to have some meaning, and the right amount of time to feedback into real world decisions. But what is that Goldilocks zone?

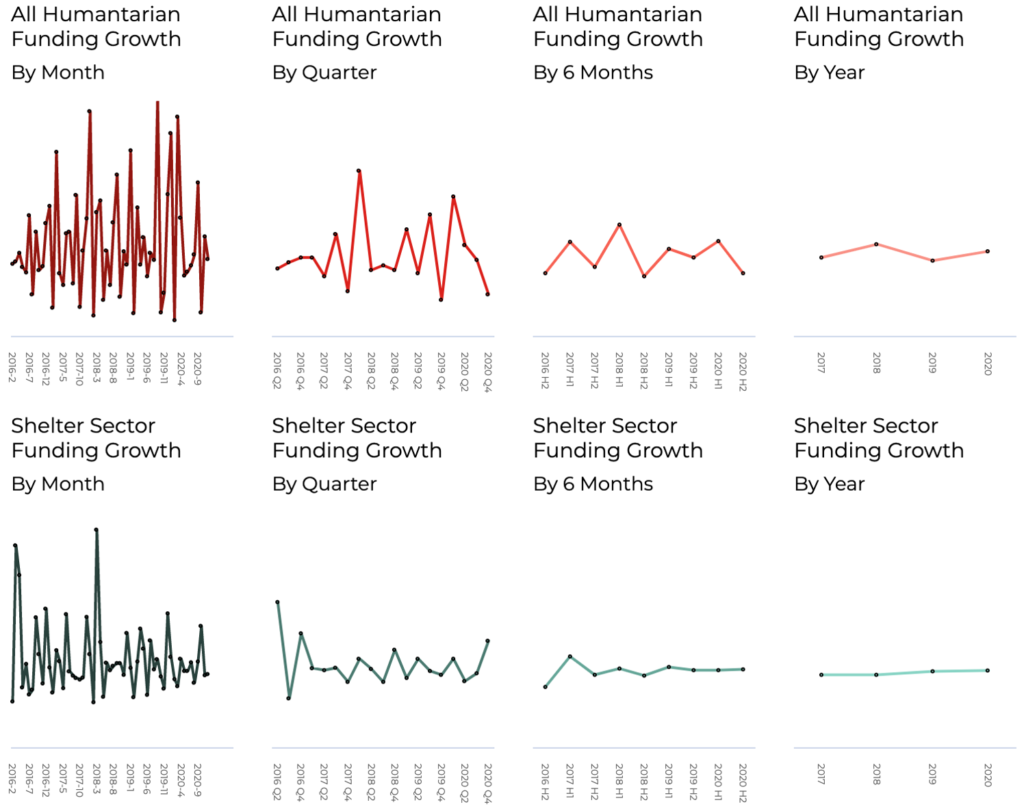

We’ve examined ‘All Humanitarian’ funding growth, as well as Emergency Shelter and NFI (‘Shelter’) sector funding growth over the period of 2016 and 2020. We’ve looked at Shelter funding as the deviations from the average aren’t so fantastical as other sectors, so we can better represent our conclusions visually.

Let’s take each of our criteria in turn. Firstly, volatility. The graphs above show that the volatility of funding growth is really quite high on a monthly and quarterly basis. The standard deviation – that’s a measure for how spread out the numbers are – for growth on a monthly basis is 68% – compared to 43% on a quarterly basis, reducing to 21% every 6 months, and then 9% every year.

High variations in growth numbers from the average wouldn’t provide us much insight, and growth of +80% followed by -63% the following month (as is the case at one point for ‘All Humanitarian’ funding) don’t tell us anything about how the funding system actually is in reality. For example, if we were to use the definition of two consecutive months of negative growth, we would have had 7 recessions since 2016 for all funding, and 9 recessions for Shelter funding. We’ll rule out monthly and quarterly at this stage.

Secondly, is six months or a year too long a period, rendering a ‘recession’ meaningless? If we were to define a humanitarian recession as either two consecutive six months of negative growth, or two consecutive years of negative growth, that’s not so long that there would never be a recession. Across the 2016 to 2020 period, ‘All Humanitarian’ funding didn’t suffer a recession as defined by two consecutive years of negative growth, but Shelter funding did suffer 3 recessions. This shows that consecutive years isn’t too long for our measurement.

So deciding between two consecutive six months, or two consecutive years, of negative growth comes down to how it would feedback into decision making. This is where we come down on the side of two consecutive years of negative growth. Organisations and donors tend to operate on annual planning and budgeting cycles (at least we’re not aware of any organisations working on shorter cycles). Defining a humanitarian recession as two consecutive years of negative growth means that there can be a yearly update to whether funding is in a recession, which aligns with the yearly updates organisations make to their budgeting and planning cycles. This means that, in theory, humanitarian actors can adjust yearly plans and resource allocation, according to yearly updates on growth and recession.

To summarise, here’s how we’re defining a ‘humanitarian recession’:

- For both technical and real definitions:

- We will exclude pledges

- We will exclude multiple year funding

- A recession is to be defined by two consecutive years of negative growth

- Technical humanitarian recession encompasses as much humanitarian funding as possible. We’ll only exclude funding if it’s not been attributed to a Response Plan, Emergency, or Location.

- Real humanitarian recession is defined by need. Only funding going to a plan that is included in the Global Humanitarian Overview is included here, as these plans have defined needs, and we can compare this to the funding required. The growth figure is given by the following formula: growth of funding minus growth of funding required. Therefore, if growth of funding is less than growth of funding required for two years in a row, that’s a recession.

Which sectors are in a recession?

The Coordination sector, Multi-Sector funding, and the WASH sector are all in recessions, both technical and real. The gap in the growth of funding vs. funding required for these three sectors widened quite drastically in 2020. Growth in funding required outpaced funding growth by 36% for Coordination, 74% for Multi-Sector funding, and 53% for WASH.

Child Protection, Health and Education are all in real recessions (that’s compared to need), despite technical growth for both Child Protection and Health.

Most other sectors are ‘In Danger’ of experiencing a real recession – that’s one year of negative growth. This includes ‘All Humanitarian’ funding, Agriculture, Gender Based Violence, Camp Coordination / Management, Food Security, Mine Action, Nutrition, Early Recovery, Shelter, and Logistics. For all of these sectors, the growth in funding required was greater than growth in actual funding. That means that the funding gap in each of these sectors will have widened in the last year.

Only two sectors increased their funding at a greater rate than the funding required. These were the Emergency Telecommunications sector, and the Protection sector.

In a year of the COVID-19 pandemic, needs across sectors grew a lot, and so did the funding required to meet those needs. But funding unfortunately didn’t keep up at the same rate, hence ‘real growth’ only occurred in two sectors.

Looking at ‘technical’ recessions and growth, the picture is slightly different. Emergency Telecommunications, ‘All Humanitarian’ funding, Agriculture, GBV, Child Protection, and Health funding all grew in 2020.

On the other hand, Early Recovery, Shelter, Logistics, Coordination, Multi-Sector, WASH, and Housing Land and Property funding have all declined for two years in a row.

Influencing decision making

Developing the ‘what equals a humanitarian recession’ framework is quite straight forward. The trickiest bit, however, is converting the statement, “Hey everyone, WASH is in real humanitarian recession”, into actual action. As we said above, being able to say the economy is in a recession is a useful shortcut for us to understand that something needs to be done. Recession should equal action. The same is true here.

If a sector is in a recession, we should have some policy levers to pull to correct that. The trouble is humanitarian funding doesn’t operate in the same way that the real or financial economy does. There’s the ‘things we can do’ problem: humanitarian actors can’t pump money into the economy through borrowing more money, or quantitative easing. And then there’s a ‘coordination’ problem: there are many donors spread across the planet, and you’d need them to act in a coordinated way to prevent recessions. And there’s also the ‘strategic priorities’ problem: donors have different strategic priorities, and they aren’t necessarily determined by how the global funding picture looks. And lastly there’s the ‘that’s not the way we cut it’ problem: CERF has an underfunded emergencies funding mechanism, and we tend to think about things by response plan and emergencies, not sectors.

One potential remedy would be to integrate humanitarian recessions into decision making more broadly. Donors could consider the global picture on an annual basis and see which sectors are really suffering.

Another potential solution would be to create an ‘Underfunded Sectors’ funding window, much like the ‘underfunded emergencies’ at a global pooled fund level. It would solve the first problem of things we can do, and give us an additional policy lever to pull and pump money into underfunded sectors. It would get round the second problem of coordination, as pooled funds are, by their very nature, a solution to coordination. It would also get round the strategic priorities problem. In a similar way that underfunded emergencies may ‘fill in the gap’ between needs and donor priorities, so could an ‘Underfunded Sectors’ funding window. And the last problem is just a mindset thing. Seeing sectors as distinct parts of the humanitarian ecosystem, that are necessary to fund to ensure capacity is not lost and needs continue to be met, is just a way of thinking about the problem.

As far as we’re aware, there’s not any large scale mechanisms to ensure sectors aren’t in a humanitarian recession (if you do know of some, please comment below to start the conversation). Something like an ‘Underfunded Sectors’ funding window would go some way to solve this.

So that’s on the donors side of things. Then there’s the other side: the Global Clusters. Global Clusters can use the framework to advocate with donors to increase funding to their sectors. There’s two tools: ‘technical recession’ and ‘real recession’. We can use these tools to influence donors to increase funding. Using a term like ‘recession’ has the potential to be a good advocacy tool, as it shortcuts the miasma of graphs and charts, and tells someone, in plain language, that the situation is not good. And, just like in a normal recession, action needs to be taken to remedy it.

Caveats, Sources and Credits

Numbers on this story may differ from numbers on the ‘Sector’ pages. This is not an error, but simply due to different data extraction dates from FTS.

FTS. Data Search. All 2016 funding. Retrieved from here

FTS. Data Search. All 2017 funding. Retrieved from here

FTS. Data Search. All 2018 funding. Retrieved from here

FTS. Data Search. All 2019 funding. Retrieved from here

FTS. Data Search. All 2020 funding. Retrieved from here

FTS. 2016 Appeals. https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/overview/2016

FTS. 2017 Appeals. https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/overview/2017

FTS. 2018 Appeals. https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/overview/2018

FTS. 2019 Appeals. https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/overview/2019

FTS. 2020 Appeals. https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/overview/2020